Este medio se sostiene gracias a su comunidad. APOYA EL PERIODISMO INDEPENDIENTE .

The sea is full of microorganisms. Smaller than one millimetre and often composed of a single cell, they come in every shape and size imaginable, from bacteria and microalgae to protozoa. But there are also viruses – incomplete entities that need a host to replicate, and so survive.

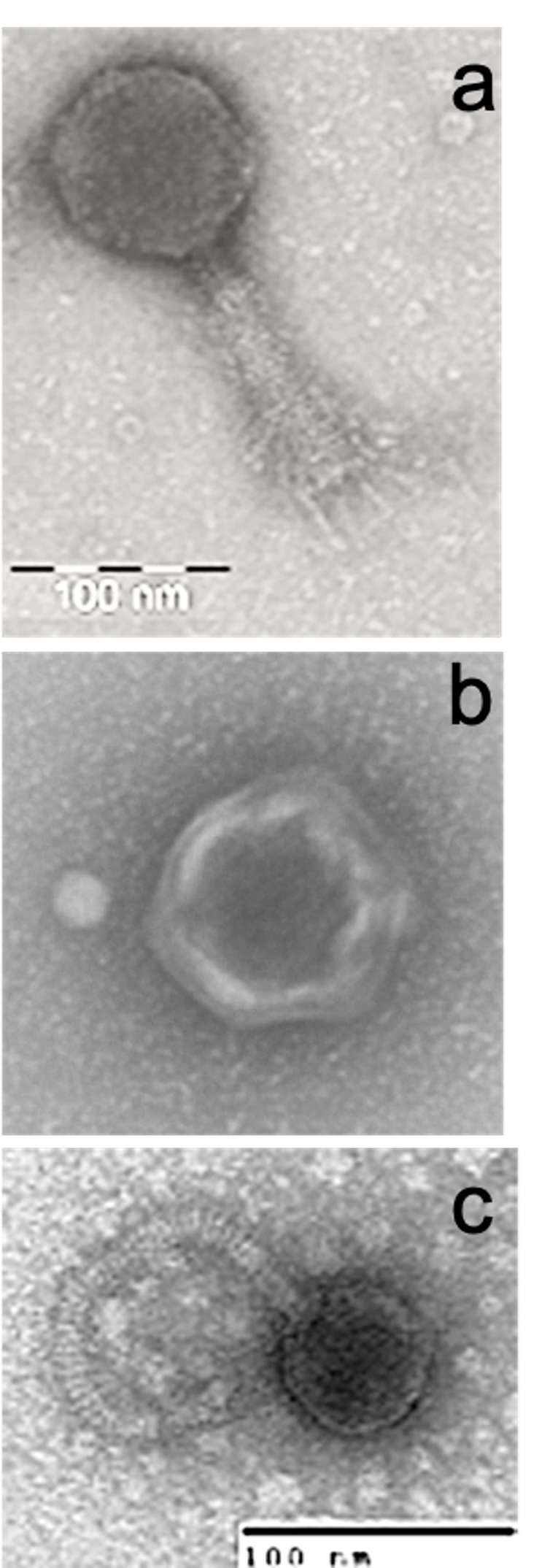

Independent virus particles have an incredibly simple structure. They’re composed of genetic material, in the form of either DNA or RNA, and surrounded by a protein shell. Each measures between 20 and 200 nanometres.

Though they may seem insignificant, viruses are the most bountiful entities in the ocean. Just one millilitre of coastal water taken from the ocean’s surface can contain up to 10 million viruses. The number of viruses decreases further offshore and deeper into the water, and as we reach the open sea, there are likely to be around 100,000 viruses per millilitre at a depth of 4,000 metres.

More viruses than stars

It’s estimated that the oceans contain one nonillion viruses – that’s a number equal to one followed by 30 zeroes, which is many more than the stars in our galaxy, the Milky Way. So how can so many survive?

This story is part of Oceans 21

Our series on the global ocean opened with five in-depth profiles. Look out for new articles on the state of our oceans in the lead up to the UN’s next climate conference, COP26. The series is brought to you by The Conversation’s international network.

While this number remains more or less constant over time, countless viruses are eaten by microorganisms or deactivated by radiation, while countless more burst forth from infected hosts. A dynamic balance exists between the disappearance of viruses and the appearance of new ones in seawater.

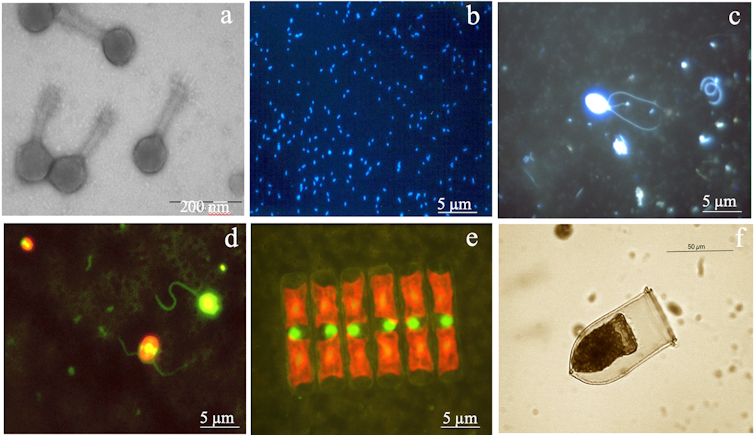

Most marine viruses have double-stranded DNA and belong to one of three families: Myoviridae, which feature long tails that can contract; Syphoviridae, which have a curved, non-contractile tail; and Podoviridae, with very short, non-contractile tails.

Viruses and their victims

Marine viruses are generally considered to be microbe killers. Once a virus has encountered a host cell, it identifies it by the cell’s surface receptors and inserts its genetic material and hijacks the machinery inside the cell in order to replicate. Following lysis (rupture of the cell membrane), some 20 to 300 viruses per cell may be shed, each of them ready to infect a new host.

Marine viruses can infect any organism, from bacteria to whales. But the abundance of ocean bacteria – 1 million per millilitre of seawater, making them the most dominant microorganism in the ocean – means that bacteria are their most likely hosts.

It’s estimated that 10²³ (the number ten, followed by 23 zeroes) viral infections occur in the sea every second, releasing new viruses but also 10⁹ tonnes of carbon from the cells they burst. In the entire ocean, viruses release around 140 gigatonnes of carbon a year as a result of this process.

On occasions, the virus does not disrupt the host it infects, but rather inserts part of its genome into the host’s DNA. These viruses are known as prophages, or lysogenic viruses, which can control what genes the host expresses and even its metabolism. But when a lysogenic virus detects an adverse shift in the environment, or if the host is defective, the prophage becomes virulent and destroys the host cell.

Each new infection offers the potential to introduce new genes into the host, and each new progeny of viruses that is shed may have stolen genes from the host. In this way, viruses are the greatest reservoir of diversity in the ocean.

The role of viruses in the ocean

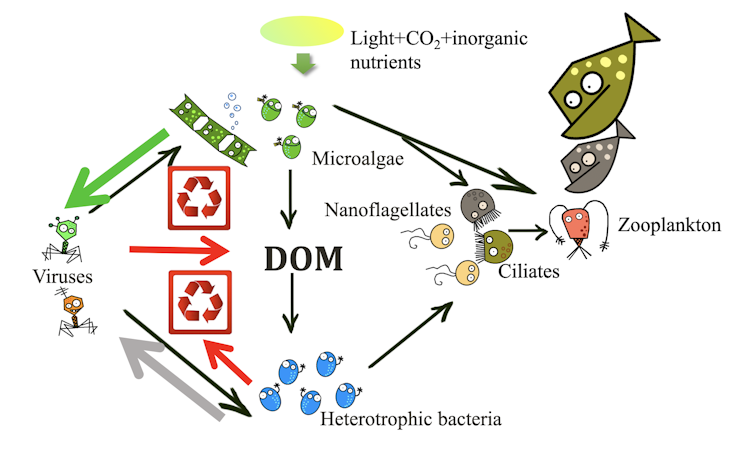

Marine viruses form part of the microbial food web and help control the abundance and diversity of bacteria and algae.

It’s estimated that viruses kill about 20% of all ocean microbes each day. Besides producing new viruses, rupturing these bacterial and algal host cells releases the material contained within, which remains in the water column as dissolved organic and inorganic nutrients.

This dissolved matter will be used again by other microorganisms to grow, which will be eaten by larger creatures, such as zooplankton and fish, which will, in turn, be eaten by sharks, whales and humans. In this way, microscopic viruses recycle the materials necessary for life to flourish. And since the ocean covers over 70% of Earth’s surface, they strongly influence life on much of this planet.

![]()

Dolors Vaqué no recibe salario, ni ejerce labores de consultoría, ni posee acciones, ni recibe financiación de ninguna compañía u organización que pueda obtener beneficio de este artículo, y ha declarado carecer de vínculos relevantes más allá del cargo académico citado.

The Conversation. Rigor académico, oficio periodístico

Este periodismo no lo financian bancos ni partidos

Lo sostienen personas como tú. En un contexto de ruido, propaganda y desinformación, hacer periodismo crítico, independiente y sin miedo tiene un coste.

Si este artículo te ha servido, te ha informado o te ha hecho pensar, puedes ayudarnos a seguir publicando.

Cada aportación cuenta. Sin intermediarios. Sin líneas rojas impuestas. Solo periodismo sostenido por su comunidad.

Related posts

SÍGUENOS

Trump y la guerra: el gran incompetente al descubierto

Un presidente que bombardea primero, inventa excusas después y convierte la política internacional en un espectáculo de irresponsabilidad.

Vox está a punto de saltar por los aires

El exsecretario general Javier Ortega Smith denuncia irregularidades económicas internas y apunta a una red de contratos opacos y poder concentrado que amenaza con hacer estallar la ultraderecha española desde dentro.

El mundo que conocíamos ha muerto

La ofensiva militar de Estados Unidos e Israel contra Irán confirma el colapso del orden internacional basado en reglas y abre paso a una política global gobernada por la fuerza.

Vídeo | Trump, ese hombre de paz que bombardeó medio planeta

Cuando el país atacado no puede responder, no es defensa. Es una guerra unilateral.

Vídeo | Quieren condenar a muerte a las mujeres que abortan en Estados Unidos

Del control del cuerpo al control de la vida y la muerte: la extrema derecha cruza una línea que creíamos impensable

Seguir

Seguir

Seguir

Seguir

Seguir

Seguir

Subscribe

Subscribe

Seguir

Seguir